Special Feature: Domestic Japanese Perspectives on Defence

[Twice monthly ‘Special Feature’ posts will feature historical, cultural, or theoretical discussions of Japanese security.]

A Brief History of Japanese Defence in Context

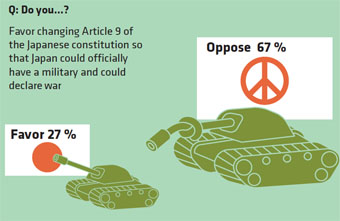

Emerging from the Second World War, humiliated by defeat and as the first nation to fall prey to the atomic age, Japan was left with the nationalistic former representatives of the wartime state and the left-wing antimilitarist pacifists scarred by their wartime experience. The American occupation authorities at GHQ purged war criminals from the government and its institutions and tried to ensure that Japan would not rearm as Germany had after the Great War. Through negotiations between GHQ and the Japanese government, they crafted their answer in Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution (1947):

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. 2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized. [1]

Article 9 was only possible through the security guarantees provided by the American occupation, but the idealism of this paragraph was shattered by the realities of the Cold War. The Korean War forced the creation of the National Police Reserve in 1950, which was reorganised into the National Safety Force in 1952, before being formed into the Self-Defense Force in 1954. Each change in name and mission pushed the boundaries of Article 9 and increased the friction between the autonomists – who wished for rearmament – and the antimilitarists – who were unwilling to see Japan be dragged into war again. The antimilitarists were also against the US military protection that guaranteed Japan its security, and their historic opposition to the 1960 renewal of the 1951 Treaty of Mutual Security and Cooperation that led to the resignation of the Kishi cabinet.

As Japan sought to find its feet in the postwar world, it was guided by a general vision promoted by Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, later known as the Yoshida Doctrine. This saw defence from the position of Mercantile Realism: let the US provide security for Japan and instead focus the national effort on rebuilding the economy. This was the dominant defence mindset until Japan’s ‘chequebook diplomacy’ raised US ire in the Gulf War.

As a economic powerhouse, and with much talk of Japan ‘overtaking’ the US, the US pushed Japan to make ‘physical’ contributions to global security, and Japan responded by pushing through the International Peace Cooperation Law (1992). The ‘PKO Law’ allowed the SDF to take part in international peacekeeping operations as non-combatants, significant because it allowed Japanese boots on foreign soil for the first time since the Second World War.

One of the proponents of the PKO Law was the now much-maligned Ichiro Ozawa (then a powerful LDP figure). In 1993, Ozawa published ‘Blueprint for a New Japan‘ in which he called for Japan to become a ‘normal nation’, that is one with an active security role, particularly in UN-guided global security activities.

Prime Minister Jun’ichiro Koizumi did more to ‘normalise’ Japan than any other prime minister to date, at least in terms of precedents. Under a series of Special Measures Laws, he allowed the Coast Guard to sink a suspected North Korean spy ship, dispatched SDF units in support of reconstruction efforts in Iraq, and helped logistical efforts in the Indian Ocean. Since Koizumi’s departure from office, the mission of equal significance has been the dispatch of MSDF vessels to the coast of Somalia in anti-piracy efforts.

As Japan faces the threats of rising China, and the nuclearisation of the Korean peninsula, it will no doubt undergo further changes. How these changes develop will depend on the views of the people who guide them.

Major Perspectives on Defence

Japan has several major schools of thought regarding the role of Japan and the SDF.*

Pacifists are typically still opposed to the existence of the SDF, which they regard as unconstitutional and a military in anything but name. They hold Article 9 as sacred, and also reject the need for a US military presence in Japan. The key political proponents of this philosophy can be found in Japan’s left-wing parties, namely the Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party.

Middle-Power Internationalists adhere to the Yoshida Doctrine and see the US security alliance as essential to maintaining Japan’s role as a global economic power. They are likely to be open to continuing Japan’s UN-based multilateral security role, but fall short of allowing Japan to have a ‘normal’ military. There are fewer Mercantile Realists these days, but the LDP’s Yasuo Fukuda, Yohei Kono and Koichi Kato could be said to be one of them.

Normal Nationalists are the dominant force in Japanese politics at the moment. They are follow the spirit of Ozawa’s ‘normal nation’ philosophy and are willing to reinterpret the constitution and SDF to improve burden-sharing within the alliance. Like the middle power internationalists, they are supportive of Japan’s international security role but are typically less enthusiastic about the US military presence. Their ultimate goal is for Japan to be an equal partner of the US. The leadership of Democratic Party is most typically associated with a softer version of this perspective, particularly Ozawa himself and former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, concerned with international security, while the neo-conservatives of the LDP, Shinzo Abe and Taro Aso, follow a more hawkish perspective.

Neo-Autonomists seek a full constitutional revision to allow a full-spectrum military capable of offensive as well as defensive operations. They are the only group likely to be open to a change in the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, seeking independence from the US nuclear umbrella. They are also likely to view the US presence as a violation of Japanese sovereignty. There are few neo-autonomists in government, but Takeshi Hiranuma, Terumasa Nakanishi and Shintaro Ishihara are among them.

[*The labels come from Richard Samuels’ “Securing Japan” (2008) research, with some further help from Tsuyoshi Sunohara’s discussion of ‘Japan’s shifting security orientation’.]

Japan Today

As it currently stands, Japan is heading towards the ‘normal nation’ that Ozawa envisioned. Pacifism is a much-valued principle that many Japanese citizens still support (at least in principle), but its support has been eroded as the US pushed Japan to secure itself in the Cold War. The Yoshida Doctrine fell by the wayside in the 1990s as Japan adapted to the ‘New World Order’ and Internationalism. Since Koizumi’s time in the Kantei, the normal nationalists have made great strides, although the balance between ‘normal’ and ‘independent’ is a delicate one. As Japan faces up to future threats, the balance could tip. Of any nation, the US holds the key in preventing Japan from remilitarising in earnest, but the final decision will lie with the Japanese people. As it stands, autonomy is unlikely to come about anytime soon.

Related articles

- War & Educational Lapses (newasiapolicypoint.blogspot.com)

- Running on Fumes (twistingflowers.wordpress.com)

- Fireworks (ampontan.wordpress.com)

- A belated post on the Senkaku collision (twistingflowers.wordpress.com)

- Rocky US-Japan relations – but better thanks to China (newasiapolicypoint.blogspot.com)

- The perpetual infancy of the political and bureaucratic classes (ampontan.wordpress.com)

- Towards tomorrow (sigma1.wordpress.com)

- Kan maybe not so unrealistic (japanlost.blogspot.com)

Leave a comment